Updated January 21, 2026

Imprisonment in Japan: What's Japanese Jail Like?

Japan is one of the most peaceful countries in the world.

It consistently ranks as one of the world's safest countries, but what actually happens if you get in trouble with the law and land yourself in jail in Japan? Let’s just say that the country's prison system, and the prison life in Japan in general, might surprise you.

The Japanese approach to incarceration is quite strict, highly regimented, and vastly different from what you'll find in most Western countries.

Whether you're curious about how prisons in Japan work or need to understand the potential consequences of legal issues that could impact your visa status in Japan, here's what you need to know about Japan’s prison system.

In this article: 📝

What Are Prisons Like in Japan?

The Japanese prison system, officially called 刑務所 (keimusho), operates under the Ministry of Justice's Correction Bureau. As of 2019, Japan has 184 penal institutions scattered across the country, including 61 prisons, 6 juvenile prisons, 8 detention houses, and numerous branch facilities.

Japanese prisons in general follow a highly regimented, military-style approach to incarceration. The system emphasizes strict discipline, where everything from how inmates walk and talk to how they eat and sleep is prescribed. Doing things incorrectly or at the wrong time results in punishment, while good behavior earns you privileges.

Unlike many Western prison systems, Japanese facilities maintain near-complete control over inmates through this rigid structure. Guards don't carry firearms but can activate alarms to summon specialized armed personnel if needed.

In fact, you might find as few as one guard supervising 40 inmates during work periods, which shows just how effective the disciplinary system is at maintaining order.

The conditions of each prison vary depending on the facility, but all prisons share common characteristics, such as minimal contact with the outside world, limited personal freedom, and an intense focus on work and rehabilitation programs.

A Day Behind Bars: Prison Life in Japan

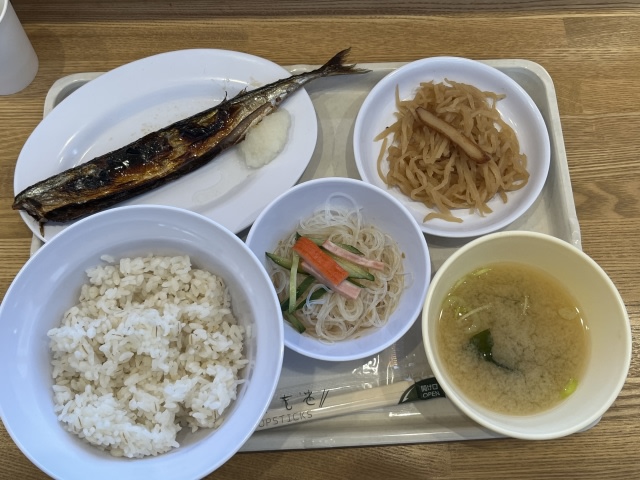

Life in a Japanese prison follows an incredibly strict timetable. At Fuchu Prison, Japan's largest male facility, a typical day looks like this:

6:45 AM - Rise and roll call

7:05 AM - Breakfast

7:35 AM - Proceed to workshops

8:00 AM - Resume work

9:45 AM - Break time

10:00 AM - Resume work

12:00 PM - Lunch

12:45 PM - Resume work

2:30 PM - Break time

2:45 PM - Resume work

4:40 PM - Return from workshops to cells

4:55 PM - Roll-call

5:00 PM - Dinner

6:00 PM - Free time

9:00 PM - Sleep

As you can tell, this schedule leaves little room for deviation. Even during "free time," inmates remain under constant supervision and can only engage in approved activities. Inmates can access radio and television, read books, or participate in physical exercises, but only at prescribed times and under a watchful eye.

For female inmates at Tochigi Prison, the schedule is similar but slightly less harsh overall. The female inmates wake up at 6:30 AM and have lights out at 9:00 PM, with a comparable work schedule throughout the day.

The rigidity of this routine has multiple purposes other than punitive. It maintains order, develops discipline, and prepares inmates for reintegration into society by allowing them to gain structured habits.

Prison Work: More Than Just Passing Time

Work is a central component of life in Japanese prisons. For those sentenced to imprisonment with forced labor, working eight hours per day is mandatory. However, a major reform that took effect in June 2025 has changed this landscape significantly.

For one, the revised Penal Code removed the distinction between imprisonment with labor and without, making prison labor no longer mandatory.

This is a historic reform, and is the first significant change to Japan's criminal punishment system since 1907. It shifts the primary goal of imprisonment from punishment to preventing repeat offenses through rehabilitation, and is actually a whole new approach to criminal punishment in Japan.

Types of Prison Work

Japanese prisons offer four main categories of work.

Production work includes manufacturing tasks where inmates create goods using state-provided materials, work with business materials, or provide labor for contract partners. Common industries include woodworking, printing, dressmaking, metalwork, and leather craft.

Social contribution work involves labor that helps inmates feel they're contributing to society, which aids in their rehabilitation and eventual reintegration.

Vocational training is perhaps the most valuable form of prison work. Inmates can acquire licenses and qualifications in 48 different fields, including welding, construction machinery operation, forklift driving, information processing, telecommunications, hairdressing, and caregiving. Some facilities even offer specialized training through private companies.

Finally, self-employed work covers tasks necessary for running the facility itself, like cooking, laundry, cleaning, and facility repairs.

Work Compensation

Inmates receive incentive remuneration for their work, though the amount is modest, to say the least.

The average monthly payment per person is approximately 4,340 yen (around $30-40 USD). This money can be used to purchase daily necessities or sent to family members, with any remaining balance given upon release, of course.

Like in many other legal systems, all income generated from contracts between the prison and private companies belongs to the government treasury.

Understanding Treatment Indexes in Prisons in Japan

Japanese prisons use a sophisticated classification system called "treatment indexes" (処遇指標) to categorize inmates based on their individual characteristics and rehabilitation needs. This system ensures that each prisoner receives appropriate treatment based on their specific situation.

The main categories include:

A and B Classifications: Based on the degree of criminal tendencies, where "A" indicates less advanced criminal tendencies and "B" indicates more advanced ones.

W Classification: Designates female inmates.

F Classification: This is particularly important for foreign prisoners. The "F" index applies to foreigners who require treatment different from Japanese inmates, specifically those who have insufficient ability to understand or express themselves in Japanese, or who have customs and habits markedly different from Japanese people.

These classifications can be combined. For example, a foreign woman with low criminal tendencies would be classified as "W-F-A."

Fuchu Prison: Japan's Largest Facility for Foreign Inmates

Fuchu Prison in Tokyo stands as Japan's largest penitentiary and houses the biggest population of foreign prisoners in the country, with over 300 foreigners representing more than 40 nationalities.

In time, the facility has adapted its operations to accommodate cultural differences, nowadays offering services like Japanese language lessons, access to an English-language library with over 8,000 books and magazines, and consultations with foreign embassy staff and non-Japanese religious representatives.

Upon admission, all inmates undergo a 15-day orientation and assessment period where they learn the rules and regulations and are evaluated for their skills and personality profiles. This assessment determines their work assignments and treatment programs.

What Happens After Prison?

Japan's approach to rehabilitation emphasizes community reintegration through several mechanisms:

Probation serves as a form of community corrections where offenders receive instruction, supervision, guidance, and assistance to become productive members of society. Professional probation officers and volunteer probation officers work together to support five types of people: juveniles on probation, parolees from juvenile training schools, parolees from penal institutions, persons with suspended sentences, and parolees from women's guidance homes.

Parole allows inmates to be released before completing their full sentence, provided they demonstrate genuine reformation. Inmates must serve at least one-third of their sentence (or ten years for life sentences) before becoming eligible. Regional Parole Boards make these decisions based on comprehensive assessments.

Coordination of Social Circumstances helps prepare inmates for reintegration by researching and coordinating post-release housing, employment, and living environments. This practical support significantly improves the chances of successful reentry into society.

Finally, pardons offer another path, including special pardons (which nullifies convictions), commutation of sentences, remission of execution, and restoration of rights lost due to criminal convictions.

The new 2025 reforms have introduced 24 new correctional courses specifically designed to address individual characteristics. These programs tailor rehabilitation to factors like age, nationality, addiction history, and mental or physical health, emphasizing the shift toward a more humane punitive system further.

Foreigners in Japanese Prisons

In 2023, 2,128 foreign inmates were admitted to penal institutions in Japan, showing a 2.4% decrease from the previous year. Foreign prisoners make up roughly 6% of Japan's total prison population, and this proportion continues to grow.

For F-index inmates (foreign prisoners requiring special treatment), Japanese prisons provide accommodations that consider their culture, lifestyle, and other factors. However, the isolation can be particularly challenging for foreign inmates, who often face language barriers and cultural differences on top of the regular hardships of incarceration.

Most foreign men convicted in Japan end up at Fuchu Prison, while foreign women typically serve their sentences at Tochigi Prison in Tochigi Prefecture. Thankfully, these facilities offer some English-language materials and access to consular representatives, but communication is still a significant challenge for many despite all of this.

Immigration Detention: A Different Type of Confinement

While we’re on the subject, it's important to distinguish between criminal prisons and immigration detention facilities. Lte’s talk about it.

If you violate immigration laws, either through overstaying your visa, working illegally, having your residence status revoked, or committing certain criminal acts, you may face detention by the Immigration Services Bureau rather than being sent to a traditional prison.

Immigration detention facilities operate separately from the prison system and focus specifically on violations of the Immigration Control Act that may lead to deportation. The conditions and procedures differ significantly from criminal incarceration, though both involve loss of freedom and strict oversight.

Recent Prison Reforms: A Brand New Direction

We briefly mentioned the significant changes that are being made on the Prison system and how punishments are carried out, but June 2025 marked an especially important moment for Japan's correctional system.

For the first time in 118 years, Japan overhauled its prison system with reforms emphasizing rehabilitation over punishment. This change addresses the country's high recidivism rates by dedicating more time and resources to educational and rehabilitative programs.

The reform eliminates mandatory prison labor, allowing facilities to focus on programs that address individual needs, whether that's geriatric care for elderly inmates with dementia, addiction treatment for drug offenders, or specialized education programs.

What’s more inmates are now categorized into 24 groups based on age, nationality, addiction history, sentence length, and other factors, with each group receiving tailored rehabilitation programs.

Critics had long pointed to Japan's rigid penal practices, and international organizations frequently called for reforms to make the system more humane. So, these changes represent Japan's commitment to modernizing its approach to criminal justice while reducing repeat offenders through support and behavioral change rather than punishment alone.

A Word About Self-Defense in Japan

Before we wrap up, here's an important warning: Self-defense laws in Japan are extremely strict, and what might be considered reasonable self-defense in other countries could very well land you in legal trouble here.

Under Article 36 of the Japanese Penal Code, self-defense must be immediate, unavoidable, and proportionate to the threat.

If you retaliate in a fight, even if you were attacked first, you risk being arrested and charged with assault or injury. Japanese law strongly emphasizes de-escalation and retreat over physical confrontation. So, what feels like defending yourself can easily be viewed as mutual violence by authorities, potentially resulting in fines, detention, or even imprisonment.

Our best advice? Walk away whenever possible. You just don’t want to have to deal with the ciriminal justice system no matter where you are in the world.

Conclusion: Understanding the Reality of Prisons in Japan

The prison system in Japan represents one of the most structured and disciplined correctional systems in the world.

From the moment inmates wake until lights out, every minute is scheduled and monitored. Work programs, rehabilitation courses, and strict behavioral expectations define daily life, all aimed at maintaining order and preparing prisoners for eventual release.

The 2025 reforms signal an important shift toward rehabilitation over pure punishment, with individualized programs addressing everything from addiction to aging-related needs. For foreign inmates, the system provides some accommodations, but language barriers and cultural differences continue to make the experience particularly challenging.

Whether you're living in Japan or just learning about the country, understanding how seriously Japan treats its laws, and the consequences of breaking them, is essential. The criminal justice system here doesn't offer much leniency, and even minor violations can have serious implications for your life, as well as your legal status in the country.

So stay informed, follow the rules, and if you ever face legal issues, seek professional help immediately. If you have further questions about criminal law troubles, make sure to check out our post on getting arrested in Japan.

Get Job Alerts

Sign up for our newsletter to get hand-picked tech jobs in Japan – straight to your inbox.